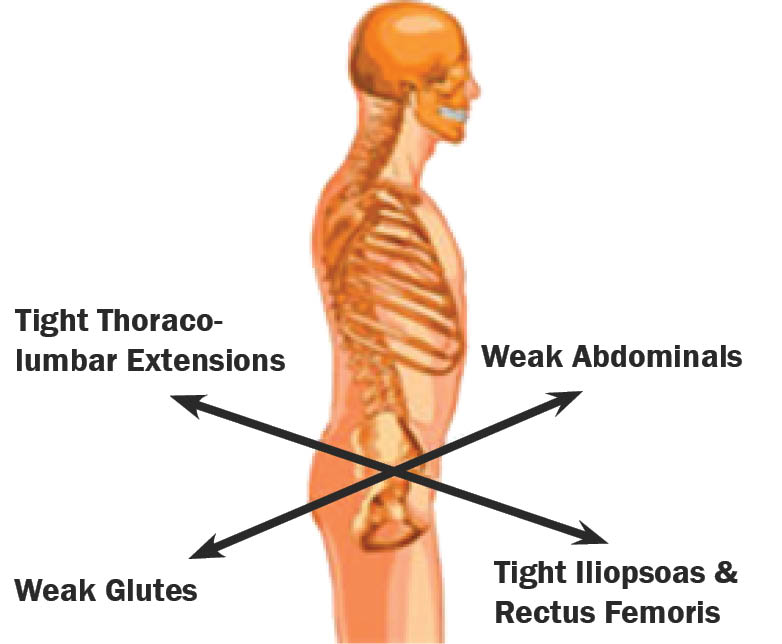

Like the Upper Cross Syndrome (discussed in the previous article), the Lower Cross Syndrome (LCS) is one of the most common compensatory patterns and a postural disorder in the lower back, pelvis, and hip joints of the muscles. The ‘Unterkreuz syndrome’ is also known as pelvic crossed syndrome, Lower Crossed Syndrome or Distal Crossed Syndrome.

‘Cross’ refers to the overactive muscles’ (and possibly tight and shortened) crossing pattern with the underactive (and possibly lengthened and weak) muscles’ counter crossing. In LCS, it is characterized by individuals displaying a postural lordotic posture more often with a protruding stomach. Prolonged sitting or injury may lead to development of shortened hip flexor muscles, and that leads to tightened lower back muscles. The tightened hip flexors eventually lead to weakened abdominal/core muscles, along with weakened gluteal/butt muscles. The impact of these muscles on the thigh and spine is common. Their postural impact on the pelvis, however, is fundamentally more important and needs to be addressed first.

Patients with LCS may experience pain in their lower back. Pain is usually not immediate in this disorder; the patient feels low back pain when this condition has stayed uncorrected for a while. LCS is often caused by an overly sedentary lifestyle and/or poor posture. Another potential cause is overtraining certain parts of the body while undertraining others. For instance, if a person strengthens their hip flexors and back without focusing on their glutes and abdominals, this could lead to an imbalance. Many who start exercising without correct guidance end up doing more harm than good. With prolonged standing, intensified pain is experienced and flexion (forward bending) alleviates it. Except in the case of a related piriformis (a muscle in your buttocks) syndrome where people feel sciatic type pain, there is no radiation of pain (pain experienced in legs) and no neurological effects. The patient finds it uncomfortable to lay with stretched legs and prefers to lie with their knees bent.

LCS should not be left untreated. It is best to treat LCS under the supervision of a physiotherapist who could monitor chronic symptoms and prescribe a personalized regimen of treatment. To diagnose, he/she will perform some clinical physical tests along with a thorough postural examination. To recover natural joint mobility, the locked joints of the hip, pelvis, and lumbar area (lower back) may be adjusted by one or more adjustments (manipulation). With this treatment you see changes in discomfort and improvement in function rapidly. This would be paired with coordinated stretching and strengthening of the muscles along with ergonomic conditioning.

To improve optimum muscle function and improve the postural alignment of the lower back, it is important to reinforce the muscles. First, a person should relax the muscles. To do this, they can use a foam roller and slowly roll parts of the body, such as the front and inner thighs, over it. Once a person finds a tender spot, they should hold the position for 30 seconds.

Exercise is great way to address LCS. Here are some simple Lower Cross Syndrome exercises you can do at home:

The Hip-Flexor-Stretch: Keep the body in an upright position as shown in the image and reach for the back foot, gently lifting it off the ground to feel a stretch at the front of the thigh. Repeat thrice on both sides.

The Hip-Flexor-Stretch: Keep the body in an upright position as shown in the image and reach for the back foot, gently lifting it off the ground to feel a stretch at the front of the thigh. Repeat thrice on both sides.

Lower Back Cat-and-camel Stretch: On both hands and knees, arch the back upwards, tucking bottom under and chin to chest. Extend the spine and drop back downwards. Bring the bottom back over your feet. Repeat 12 times.

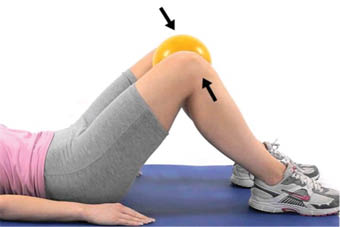

Supine Ball Squeeze: Lay on your back with your knees bent. Place a small ball or rolled-up towel between your knees. Squeeze the ball firmly with your legs and hold for 3 -5 seconds. Relax briefly. Repeat 10 to 15 times. As your strength improves, try an intermediate variation of the exercise – Place the ball between your thighs and raise your hips off the floor into a glute bridge. When your body forms a continuous line from your knees through your hips to your shoulders, hold the position and do your ball squeezes. Bump it up to the advanced level by working on one leg. Move into a two-legged glute bridge with the ball between your legs. Carefully shift your weight over one foot and extend the other leg while maintaining your grip on the ball.

Supine Ball Squeeze: Lay on your back with your knees bent. Place a small ball or rolled-up towel between your knees. Squeeze the ball firmly with your legs and hold for 3 -5 seconds. Relax briefly. Repeat 10 to 15 times. As your strength improves, try an intermediate variation of the exercise – Place the ball between your thighs and raise your hips off the floor into a glute bridge. When your body forms a continuous line from your knees through your hips to your shoulders, hold the position and do your ball squeezes. Bump it up to the advanced level by working on one leg. Move into a two-legged glute bridge with the ball between your legs. Carefully shift your weight over one foot and extend the other leg while maintaining your grip on the ball.

The Leg Extension: Lie on your stomach. Raise one leg at a time from the hips, keeping the knee straight. Repeat 12 times (1 set = 12 reps). Perform 3 sets per leg.

The Leg Extension: Lie on your stomach. Raise one leg at a time from the hips, keeping the knee straight. Repeat 12 times (1 set = 12 reps). Perform 3 sets per leg.

Bridging Exercise: Lie on your back. Pressing through the midfoot while exhaling, lift the hips and trunk off the surface. Hold for a count of 5 and return. Inhale to rest, then exhale to repeat the action. Ensure that the neutral spine is preserved and that the lumbar spine isn’t over-extended. Repeat 12 times.

Bridging Exercise: Lie on your back. Pressing through the midfoot while exhaling, lift the hips and trunk off the surface. Hold for a count of 5 and return. Inhale to rest, then exhale to repeat the action. Ensure that the neutral spine is preserved and that the lumbar spine isn’t over-extended. Repeat 12 times.

Once you get comfortable doing the above exercises and experience significant relief, you should work towards a strong core stability program, for long term gains. I plan to devote a weekend to core stability and conditioning, because its importance cannot be emphasized enough.

- Move Bawa Move!! - 15 March2025

- The Healing Power Of ‘Shinrin-Yoku’ (Forest Bathing) - 28 December2024

- The Incomparable Health Benefits Of Plant-Based Diet - 30 November2024