The eagerness of Parsis to learn and become educated in the last decade of the 19th century, coupled by the establishment of numerous educational institutions by our community, led this miniscule ethnic community to become the most literate among all Indian communities. According to the Census of India, even as far back as in the year 1911, seventy-one per cent of the Parsis living in Bombay were literate. What is more, in the year 1901, 25.8% Parsis had command over the English language, compared to 20.9% of Indian Christians, 0.95 Jains, 0.4% Hindus and 0.2% Muslims.

Coming into India from Iran, around the 8th century AD., in the wake of Arab persecution, Parsis remained largely a farming community, until the advent of the British in India, which changed the Community’s fortunes and culture. Today, Parsis are known for several traits – their love for food and humour, virtually cent per cent literacy and Parsi girls often far more educated than Parsi boys. Education and education alone has been the key to the community’s proverbial fame and to a very limited extent, its current bane.

Just as darkness has no existence of its own (darkness is merely the absence of light), Parsis believe that evil does not have an existence of its own – it is merely the absence of good. And, therefore, just as lighting a candle dispels darkness, so does lighting the mind through knowledge and literacy, dispels evil with a domino effect. Knowledge and literacy is the key that can unlock doors to socio-economic progress and prosperity.

“Parsi, thy name is charity” is a common expression that traces its roots to the time of the British Raj. When one thinks of philanthropy, the name ‘Tata’ immediately comes to mind. The patriarch of the Tata family, Jamsetji, lived in an age when philanthropy was its own reward – tax rebate for charitable donations was unknown then. Jamsetji was a man sensitive to the suffering of his people but realized that “patchwork philanthropy”, as he called it – giving some food here and clothes there – would not go far. So he formulated his philosophy on “constructive philanthropy”. He defined it thus: “What advances a nation or a community is not so much to prop up its weakest and most helpless members but to lift up the best and the most gifted, so as to make them of the greatest service to the country.” With this end in view, he launched the J.N. Tata Endowment Scheme for Higher Education in 1892, sending abroad future administrators, scientists, doctors, lawyers and engineers, and he formulated his major scheme of an University of Science (and technology) to give India the technology personnel that would enable it to step into the industrial age.

Jamsetji believed that true philanthropy should be aimed at making its recipients self-reliant and self-respecting and capable of earning their way through life by doing an honest day’s work. Educational facilities and employment opportunities could alone ensure this. His major philanthropic works had one aim – to train and equip men and women for life – to help them help themselves.

Higher education abroad, especially in areas of science and technology is expensive. Among the few trusts which extend scholarships for higher studies abroad, the two most noteworthy are the J.N. Tata Endowment and the R.D. Sethna Scholarship Fund. Between these two Parsi-endowed and Parsi-managed trusts, students of all communities even today manage to raise a large chunk of the required funds.

Always ahead of his time, Jamsetji Tata pioneered higher education among women. The first name in his register for scholarships, as far back as in 1892, was a lady medical doctor, Miss Freny K.R. Cama. She was loaned, in those days, Rs.10,000/- which, in terms of today’s money, is probably worth thirty times the amount. She returned as one of India’s pioneering gynecologists.

On a single page of the register of the J.N. Tata Endowment Fund for the period 1905 to 1909 appear the names of the following scholars: A.R. Dalal, who became a Member of the Viceroy’s Executive Council; J.C. Coyaji, later Chief Justice of the Bombay High Court; B.N. Rao who rose to be a Judge of the International High Court at The Hague; Dr. Jivraj N. Mehta, Chief Minister of Gujarat; noted economist Dr. Raja Ramanna and former President of India, Shri K.R.Narayanan.

Sir Ratan and Sir Dorab Tata established pioneering trusts geared to building the educational, social and scientific infrastructure of this nation. At a time when most charities were communal in nature, the Sir Ratan Tata Trust (1918) and the Sir Dorabji Tata Trust (1932) established a precedent of being universal in their generosity. The Anjuman-i-Islam or a Hindu institution could lay as much claim on its resources as any Parsi charity could – and they did.

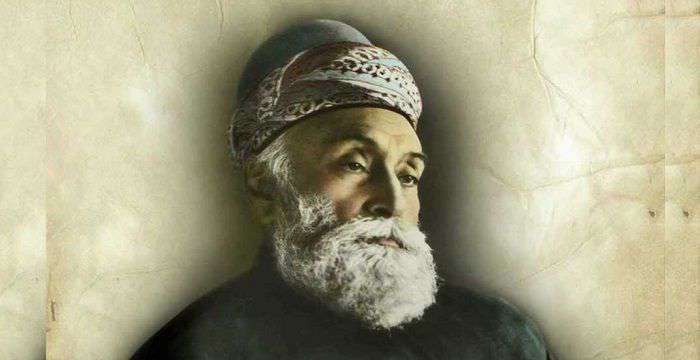

Jamsetji Tata was, no doubt, a visionary and the father of building a modern industrial India. However, the Prince of Philanthropists is, without doubt, Sir Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy – the first Indian Knight and Baronet. The extent of his philanthropy is too vast, wide and varied to be compared with any other philanthropist. His contribution to public works and charities between 1822 – 1859 aggregate Rs.24,59,736/-. It is interesting to note that out of this staggering sum (for that period of time) less than fifty per cent went to his own community – the Parsis.

At a time when primary education was lacking in India, Jamsetjee gave money to establish a School of Arts. Even today, it is the biggest school of its kind in the East. Jejeebhoy not only advocated female education, but set an example by educating his only daughter Pirojbai who became one of the first Parsi women to learn English. Jejeebhoy was convinced that education was a powerful weapon to smite all social evils and superstitions. He established 19 schools during his lifetime, five in Mumbai and the rest all over Gujarat.

There are many other Parsi families who contributed significantly to the cause of education. Sir Cowasji Jehangir Readymoney started not just a Girls’ School at Bombay but contributed handsomely towards the Elphinstone College building and the Convocation Hall at the University of Bombay. The Petit family built an orphanage for boys at Poona in 1888, the hall at the Victoria Jubilee Technical Institute and the J B Petit School as also the Bai Avabai Petit School for Girls at Bandra in Mumbai. The Patuck family established a variety of educational institutions including an Industrial School in 1934 a Technical High School in 1945, an Industrial Training Institute in 1981, a Junior College in 1981, a Primary School in 1994 and a College of Commerce and Management in 2001. The Godrej family established the Udayachal School in Mumbai. Manockjee Cursetjee established The Alexandra Girls’ English Institution which was the first school in Bombay to provide education in English to Indian girls. Bachoobai Moos’s zeal to promote education for girls led to the establishment of the Girton High School for girls in 1888.

- Celebrate Nature’s New Year With Purity And Piety of Ava - 22 March2025

- Celebrate Navruz 2025 With The Spirit Of Excellence And Wholesomeness - 15 March2025

- Celebrating Women And Equality - 8 March2025