The Egyptian Rosetta Stone is one of the world’s best-known archaeological artifacts, viewed by millions of visitors annually at the British Museum. The Stone is a broken part of a bigger stone slab, with a carved message, inscribed in three types of lettering. It was an important clue that helped experts learn to read Egyptian hieroglyphs, a writing system using pictures as signs. Because the inscriptions say the same thing in three different scripts, and scholars could still read ancient Greek, the Rosetta Stone became a valuable key to deciphering ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs.

The Egyptian Rosetta Stone is one of the world’s best-known archaeological artifacts, viewed by millions of visitors annually at the British Museum. The Stone is a broken part of a bigger stone slab, with a carved message, inscribed in three types of lettering. It was an important clue that helped experts learn to read Egyptian hieroglyphs, a writing system using pictures as signs. Because the inscriptions say the same thing in three different scripts, and scholars could still read ancient Greek, the Rosetta Stone became a valuable key to deciphering ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Deciphering Hieroglyphs

Soon after 4 AD hieroglyphs became redundant. During the early nineteenth century, scholars would use Greek inscriptions on this stone to decipher them. English physicist, Thomas Young, was one of the first to show that some of the hieroglyphs on the Rosetta Stone indicated the sound of the royal name – Ptolemy. French scholar, Jean-François Champollion, then realised that hieroglyphs recorded the sound of the Egyptian language. This laid the foundation of our knowledge of ancient Egyptian language and culture.

The Rosetta Stone derives its name from the town of Rashid, also known as Rosetta in the Nile Delta. Napoleon Bonaparte campaigned in Egypt from 1798 to 1801 and his soldiers accidentally discovered the Rosetta Stone on 15th July, 1799, while digging the foundations of an addition to a fort near Rashid. It had apparently been built into a very old wall. The officer in charge, Pierre-François Bouchard (1771–1822), realised the importance of the discovery. On Napoleon’s defeat, the stone became the property of the British, under the terms of the Treaty of Alexandria, in 1801, alongside other antiquities. The stone was shipped to England and arrived in Portsmouth in February 1802, where it was presented to the British Museum by George III in July. The Rosetta Stone and other sculptures were placed in temporary structures in the Museum grounds as the floors weren’t able to bear their weight. A plea to Parliament for funds saw a new gallery built to house these.

The Rosetta Stone has since been on display in the British Museum, except once in 1917, towards the end of WW-I, when the Museum concerned about being bombed, moved it to safety alongside other portable ‘important’ objects, for two years in a station on the Postal Tube Railway, 50 feet underground, at Holborn.

Egypt’s Rosetta Stone Inscription, though famous, the message itself is uninspiring, dealing with a banal piece of administrative business. It’s a copy of a decree passed in 196 BCE by a council of Egyptian priests, celebrating the anniversary of the coronation of Ptolemy V Epiphanes, as king of Egypt. The Ptolemaic dynasty was a Greek-speaking dynasty of Macedonian origin, that ruled Egypt from the 4th to 1st century BCE.

The text catalogues some of the king’s noble deeds and accomplishments, such as giving gifts to the temple, granting tax reductions, and restoring peace to Egypt after a rebellion during the reign of his predecessor, Ptolemy IV Philopator, as also bolstering Ptolemy V Epiphanes’ royal cult via construction of new statues, better shrine decorations, and festivals for his birthday and day of coronation. The inscriptions also say priests should be exempt from taxes as they are serving the Gods. Finally, the decree states that it should be inscribed in stone in hieroglyphics, the demotic script, and Greek, and placed in temples across Egypt. The priests understood the power of the written word and wanted it carved in stone, for all to see.

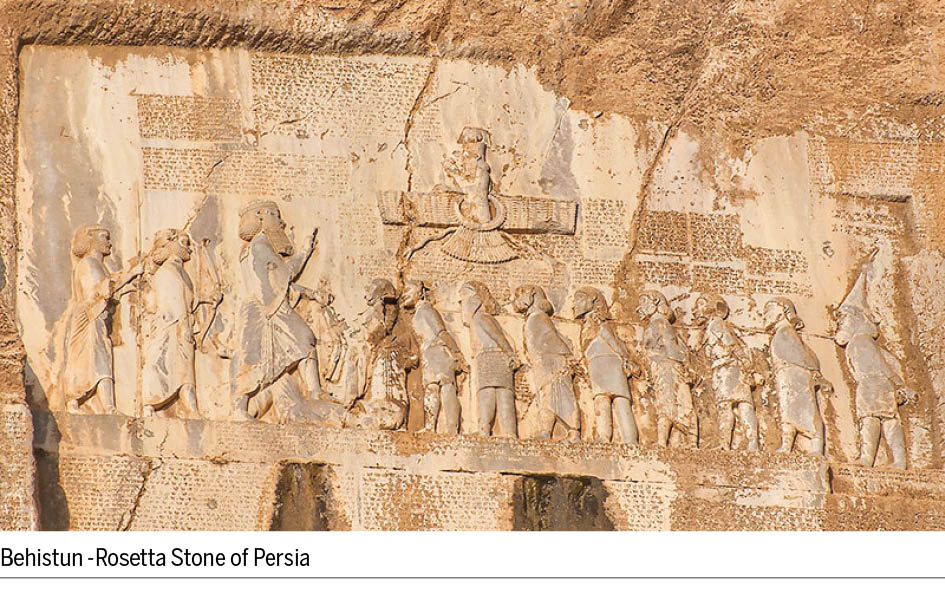

Ancient Iran’s Rosetta Stone

Far more impressive and inspiring than Egypt’s Rosetta stone is the inscription of Darius the Great, at Mount Behistun, near Kermanshah, in Northwestern Iran. Behistun (earlier Bagistanon, derived from old Persian Bagastan, meaning Land of God), is a UNESCO World Heritage site. Like Egypt’s Rosetta stone, Mount Behistun’s inscriptions are in three ancient languages – old Persian, Elamite and Babylonian.

Like the Egyptian priests, Darius the Great also understood the power of the written word and wanted it carved in stone, for all to see. The site was chosen as it was close to one of the branch roads of the ancient ‘silk trade route’, which later became the Royal Road of Darius the Great. This Royal Road of Persia was a 1,500-mile (2,400 km) road built by King Darius the Great in 5th century BCE, to connect the ancient winter capital of Susa in South western Iran to Sardis in western Turkey. The road was a major transport route, facilitating Darius to maintain control over his conquered lands.

According to historian George Rawlinson, in his book. ‘The Seven Great Monarchies’, Vol. 3, Media, “This remarkable spot, lying on the direct route between Babylon (modern Iraq) and Ecbatana (modern Hamadan), and presenting the unusual combination of a copious fountain, a rich plain, and a rock suitable for sculptures, must have early attracted the attention of the great monarchs who marched their armies through the Zagros range, as a place where they might conveniently set up memorials of their exploits.”

In 1835, George Rawlinson’s elder brother, Sir Henry Rawlinson, an army-officer of the British East India Company, began investigating this grand monument and deciphering the ancient inscriptions. The reliefs and inscriptions are a hundred metres above ground level on a limestone cliff and approximately fifteen metres high and twenty-five metres wide in size. The relief and inscriptions chronicle, for the main part, the court intrigue and rebellions that Darius had to contend with, in his ascension to the throne and the many rebellions across the Persian empire, shortly assuming the throne of ancient Iran.

The inscriptions, using the cuneiform script, lead some to call the Behistun inscriptions the Persian Rosetta Stone. The Old Persian text comprises 414 lines of text across five columns; the Elamite text consists of 593 lines of text across eight columns, while the Babylonian text consists of 112 lines. Darius mentions in the inscriptions that he had copies of the inscription written on parchment distributed through the empire. A copy of the inscription written in Aramaic was found on Elephantine Island, on the upper Nile, near Aswan city, in Egypt.

Depiction Of Authority And Legitimacy: The figures in the rock carvings are identified by inscriptions next to them. Facing the king, are nine rebels from different nations of that period, tied together with a rope around their necks and hands tied behind their backs. The tenth rebel is shown lying on the ground with King Darius’ foot on his chest, signifying conquest over his worst opponent. The scene is a declaration of the legitimacy of Darius’s claim to Cyrus the Great’s throne.

The best craftsmen of the kingdom were gathered at Behistun to carve this scene a hundred meters above ground level. In the rock inscriptions, Darius begins with a self-introduction, his ancestry and his claim to the throne as the rightful heir of Cyrus the Great, who founded the Achaemenid dynasty. He enumerates the tributary countries, which owe him allegiance: “Thus says Darius the King: These are the countries, which came unto me, by the Grace of Ahura Mazda. I became King of them: Persia, Susiana, Babylonia, Assyria, Arabia, Egypt, the (lands) on the sea, Sparda, Ionia, Media, Armenia, Cappadocia, Parthia, Drangiana, Aria, Chorasmia, Bactria, Soghdiana, Gandara, Scythia, Sattagydia, Arachosia and Maka; twenty-three countries in all… These are the countries which came unto me, by the Grace of Ahura Mazda, they became subject unto me, they brought tribute unto me, whatsoever commands I gave them by night or day, these they performed.”

To convince readers of the authenticity of his inscriptions, Darius states: “That which I have done I have always done by the Grace of Ahura Mazda. Thou who shalt hereafter read this inscription, let that which is done by me appear true unto thee; regard it not to be a lie… Let Ahura Mazda be witness that it is true and not false, all this have I done.”

“Thus says Darius the King: By the Grace of Ahura Mazda, there is much more done by me, which is not written in this inscription; for this reason it is not written, lest he who shall hereafter read this inscription, to him that which has been done by me should seem exaggerated, it may not appear true to him, but may seem to be false.”

Darius devotedly ascribes all his achievements repeatedly to the Divine help he received: “That which I have done, I have done with the Grace of Ahura Mazda. Ahura Mazda brought me help. For this reason Ahura Mazda brought me help, because I was not wicked, nor a liar, nor a tyrant, neither I nor my family.”

Indeed, ancient Iran’s Rosetta stone, in Kermanshah, is more awe inspiring than its Egyptian counterpart, which so many flock to see at the British Museum in London!

- Moon And Moods - 22 February2025

- The Joy Of Giving - 15 February2025

- Celebrate A Joyful Week Of Love - 8 February2025