Parsi Times presents a 4-part series by Adil J. Govadia, which explains the different grades of our Holy Fires and their crucial importance in our religion and our lives.

In the 14th century, after almost seven centuries of existence of the Iranshah Fire in Sanjan, Allauddin Khilji’s invading army, led by Altaf Khan, ran over the Hindus and completely demolished the town. It was then that the brave Shapur, son of the slain Ardeshir Babekhan, shifted and concealed the Iranshah Fire in one of the three caves at Bahrot hills, near Sanjan.

In the 14th century, after almost seven centuries of existence of the Iranshah Fire in Sanjan, Allauddin Khilji’s invading army, led by Altaf Khan, ran over the Hindus and completely demolished the town. It was then that the brave Shapur, son of the slain Ardeshir Babekhan, shifted and concealed the Iranshah Fire in one of the three caves at Bahrot hills, near Sanjan.

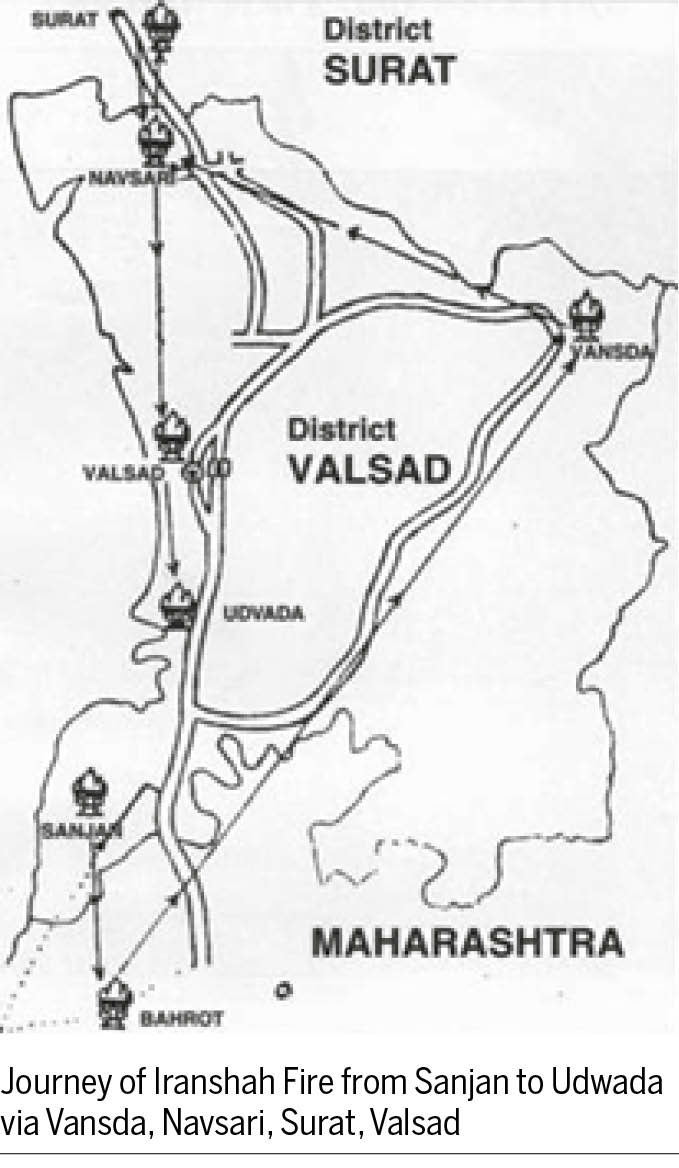

For almost 12 years, through many intrusions and invasions, the Iranshah Fire was kept safely in the Bahrot caves, tended-to devotedly with complete religious edict and fervour. Around 1405 CE, when peace returned, the Iranshah Fire was shifted from Bahrot Hills to Ajmalgadh, on the Sahyadri mountain ranges, near Bansda (Vansda, Kingdom of Shrimant Kirtidev) where it remained for 14 years. In 1419 CE, the Fire was shifted to Navsari by three courageous Sanjana priests – Khurshed-Kamdin, Nagan-Ram and Chaiyyan-Shaer, where it stayed for almost 320 years, except for three years (1733 to 1736 CE) when it was temporarily shifted to Surat due to some political unrest. Subsequently, owing to disputes between the Bhagaria and Sanjana priests, Iranshah was abruptly shifted out of Navsari to Udwada via Valsad, where it continues to radiate in full glory, since 1742 CE.

At one time, ancient Iran housed almost 24,000 Atash Behrams. However, due to several vicious invasions by the Macedonian Greeks and the Arabs, resulting in wanton destruction and brutal plundering, most of the religious institutions were not only ruined, but even the written records of how these Atash Bahrams were consecrated and installed, were lost forever. Even records of how the Iranshah Atash Bahram was conceived and consecrated are unavailable. Hence, in 1765, almost 900 years after Iranshah fire was installed, when consecration of an Atash Bahram in Navsari was considered, the elders of the Navsari Bhagarsath Anjuman invited all the ‘buzorg mobed sahebs’ (senior knowledgeable priests), well versed in ritual craft – to formally outline a ceremonial process of consecrating an Atash Bahram. After examining various sacred Avesta and Pahlavi texts and much deliberation, they finally devised a religious process to install an Atash Bahram (Ref. Dastur Firoze Kotwal and James Boyds’s ‘A Guide To Zoroastrianism’).

Establishing and consecrating an Atash Behram is a very elaborate and intricate process involving fires collected from SIXTEEN sources, namely: Cremation Fire; Dyer’s Fire; Public Bath Fire; Potter’s Fire; Brickmaker’s Oven Fire; Fakir’s Fire (a non-Zoroastrian mendicant) or Kansara’s Fire (maker of bronze vessels and utensils); Alchemist or Goldsmith’s Fire; Minting Fire (used to melt coins); Blacksmith’s Fire; Weapon Maker’s Fire; Baker’s Oven Fire; Brewer’s Fire; Army Chief’s Fire or Fire from the home of a departed Army-man; Shepard’s Fire or fire from the stables of horses and camels; Lightening Fire; and Atharwan’s Fire or fire from the hearth of any pious and virtuous Parsi layman (Behdin).

A question often asked is why include the cremation fire, especially since it is the most polluted? Through a complicated ritual process, the said fire is purified multiple times till a decontaminated essence remains. This refining process of purification is believed to please Adar Yazad immensely, perceived as a ‘sawab-nu-kaam’ (noble work). Moreover, Zoroastrianism recognizes the fact that in different fields of work and cultures (like the blacksmith and artisans), fire may not be treated with utmost care and respect. Hence, fires which have endured great hardships are often preferred, which are then taken through a purification process before using their essence for ritual purposes.

Thus, fires from above stated sixteen sources are subjected to a stringent ritualistic process of filtration, cleansing, purification and consecration. The high levels of purity observed while consecrating and enthroning an Atash Behram is a very complex and ceremonially ritualistic process, involving a total of 32 Yozdathregar Mobeds to recite and perform 1,128 Yasna and 1,128 Vendidad ceremonies consecutively and concurrently, lasting for a little over three years. It entails consecration of these sixteen fires before amalgamating and enthroning them as an Atash Behram! The consecrated Fire thus enthroned is believed to develop into a living, pulsating entity, a spiritual Monarch and Divine authority, capable of creating good fortune for the devout worshippers who stand before Him!

NOTE: While Qissa-e-Sanjan provides an overview of the Zoroastrian exodus to India, it does not give precise dates of landing nor does it refer to a Dastur Neryosang Dhaval to have existed in 721 ACE. One Dastur Neryosang Dhaval did exist in the 12th century, as per several Sanskrit translations of Pahavi texts made by him. Likewise, the consecration of Iranshah in 721 ACE is also a conceivable conjecture, as calculated by historian Shapurshah Hodivala, based on historical events. Since the Persian Zoroastrians could prophesize ‘evil to come’ 49 years before the event, one rudimentary theory is to subtract the number 49 from the last Emperor Yazdegard’s year of murder (631 ACE) and then apply the Zend Avesta and Jamaspi recordings into service. Thus, 631 ACE – 49 = 582 ACE + 100 years spent in Kohistan + 15 years spent in Hormuz + 19 years after landing at Diu and reaching Sanjan = 716 ACE – a likely year of arrival in Sanjan (Ref. Shapurshah Hodoivala’s ‘Studies in Parsi History’)”.