Wine and alcohol have been used as medicine since ancient times, and some studies suggest that moderate wine consumption may have health benefits. Sir Winston Churchill was a devoted fan of champagne, and his favorites included Pol Roger and Moet et Chandon. He once famously said, “I cannot live without Champagne. In victory, I deserve it. In defeat, I need it.” To those who called him an alcoholic, he famously said: “I have taken more out of alcohol than alcohol has taken out of me.”

Wine and alcohol have been used as medicine since ancient times, and some studies suggest that moderate wine consumption may have health benefits. Sir Winston Churchill was a devoted fan of champagne, and his favorites included Pol Roger and Moet et Chandon. He once famously said, “I cannot live without Champagne. In victory, I deserve it. In defeat, I need it.” To those who called him an alcoholic, he famously said: “I have taken more out of alcohol than alcohol has taken out of me.”

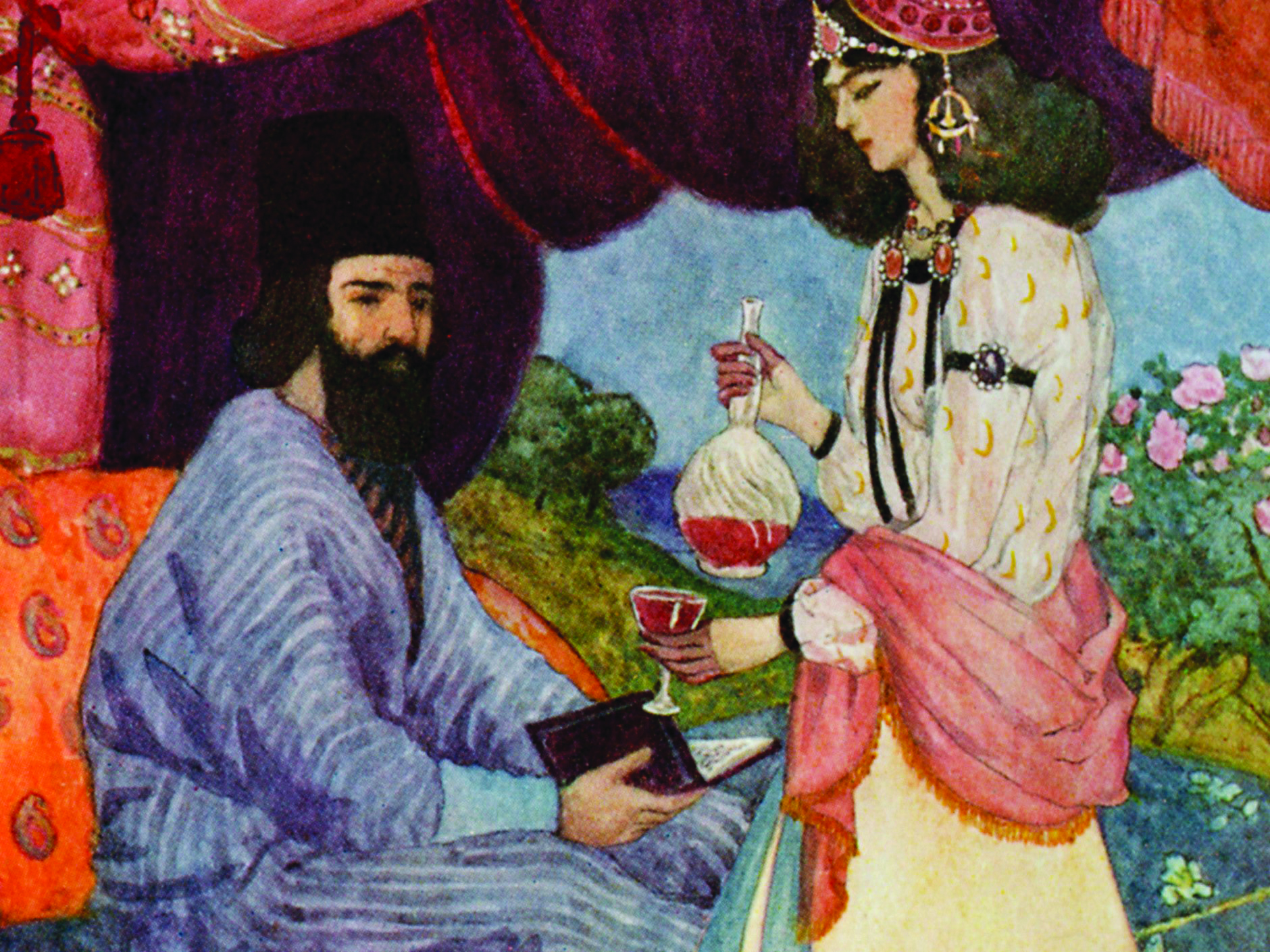

Wine As Medicine

There is a popular phrase ‘dava-daru’, which literally means medical treatment for illness with alcohol or wine as medicine. Firdousi Toosi in the Shahnameh refers to an elixir called ‘Nosh-daru’ which had the quality to heal extremely serious wounds and ailments. Early medicine was closely tied with religion and the supernatural, with early practitioners often being priests and magicians (in Persia, the Magi).

Wine’s close association with rituals made it a logical tool for early medical practices. Sumerian tablets and papyri from Egypt dating to 2200 BC include recipes for wine-based medicines, making wine the oldest documented human-made medicine. When the Greek introduced a more systematized approach to medicine, wine retained its prominent role. The Greek physician Hippocrates (also considered the father of medicine) believed wine to be part of a healthy diet, and advocated its use as a disinfectant for wounds, as well as a medium in which to mix other herbs for consumption by sick patient.

In his first century work De Medicina, the Roman encyclopedist Aulus Cornelius Celsus detailed a long list of Greek and Roman wines used for medicinal purposes. While treating gladiators in Asia Minor, Roman physician Galen would use wine as a disinfectant for all types of wounds, and even soaked exposed bowels before returning them to the body. During his four years with the gladiators, only five deaths occurred, compared to sixty deaths under his immediate predecessor.

Wine In Ancient Religious Traditions

In Ancient Egypt, beer and wine were drunk and offered to the gods in rituals and festivals. Beer and wine were also stored with the mummified dead in Egyptian burials. Other ancient religious practices like Chinese ancestor worship, Sumerian and Babylonian religion used alcohol as offerings to gods and to the deceased. Mesopotamian cultures had various wine gods and a very ancient Chinese imperial edict even declared that drinking alcohol in moderation is prescribed by heaven.

In the ancient Mediterranean world, the Cult of Dionysus and the Orphic mysteries used wine as part of their religious practices. During Dionysian festivals and rituals, wine was drunk to reach ecstatic states along with music and dance. Intoxication from alcohol was seen as a state of possession by the spirit of the god of wine Dionysus. Religious drinking festivals called Bacchanalia were popular in Italy and associated with the gods Bacchus and Liber.

In the Norse religion the drinking of ales and meads was important in several seasonal religious festivals such as Yule and Midsummer as well as more common festivities like wakes, christenings and ritual sacrifices called Blóts. In Jewish tradition, many Jews embrace a responsible approach to alcohol, often emphasized during religious observances and social gatherings. Wine is used during the Sabbath and festival meals as part of the Kiddush blessing, which sanctifies the day and acknowledges the sanctity of the occasion. Wine also plays a prominent role in the Passover Seder, where participants drink four cups of wine to symbolize the four expressions of redemption mentioned in the Torah. Moreover, wine is used in the Jewish wedding ceremony, where the bride and groom share a cup of wine under the chuppah (wedding canopy) as a symbol of their union and commitment to one another.

According to the Catholic Church, the sacramental wine used in the Eucharist must contain alcohol. In the Catholic Church, the Eucharistic wine becomes the blood of Jesus Christ through transubstantiation.

Discovery Of Wine In Pre-Historic Iran

According to legend, wine was accidentally discovered during the pre-historic reign of Shah Jamsheed of the Peshdad dynasty. A lady of the Royal Court was going through great sorrow and agonizing headaches. She felt like giving up her life and accordingly drank some liquid from a jar marked as ‘poison.’ This jar contained remnants of grapes that were considered spoiled and deemed to be poisonous. The grapes had fermented and turned into wine. After consuming this ‘poison’ the lady fell fast asleep and surprisingly woke up feeling rejuvenated. News went up to the king and grapes started to be used for wine making.

Early Iranian fermentation primarily relied on natural fermentation processes. Grapes were crushed and left in open containers, allowing wild yeast present on the grape skins to initiate the fermentation process. The yeast converted the sugars in the juice into alcohol, resulting in wine. The same natural fermentation process was employed in the production of mead and other fruit-based alcoholic beverages, where the wild yeast present in the environment would trigger fermentation

Archeologically, one of the earliest signs of wine production in Iran can be traced to the Neolithic period, around 7,000 BCE. Excavations in the Zagros Mountains, particularly at the site of Hajji Firuz Tepe, have revealed pottery vessels with residues indicating the presence of fermented beverages. These vessels have remnants of tartaric acid, a key indicator of grape fermentation. This suggests that the inhabitants of ancient Iran were fermenting grapes to produce an early form of wine

Evidence of wine production and consumption in ancient Persia can also be found in the writings of Greek historians and travelers. The Greek historian Herodotus, who lived in the fifth century BCE, documented the Persians’ fondness for wine, describing elaborate drinking customs and royal feasts where wine flowed abundantly. The writings of Xenophon, another Greek historian and soldier, provide further insight into the cultivation of grapes and winemaking process in ancient Persia.

Shiraz Wine

Today, Shiraz is a famous red wine. However, the first evidence of grape cultivation in the province of Shiraz goes back to 2,500 BC which was the period when the Achaemenians ruled over several nations. During the fourteenth century, wine was immortalized in the poetry of mystic poet Hafez, whose tomb in the city of Shiraz is venerated to this date. Later in 1680s, a French diamond merchant, Jean Chardin, travelled to Persia to the court of Shah Abbas. He attended elaborate banquets and recorded the first European account of what Shiraz wine tasted like.

Apart from grape-based wine, other fermented drinks were also prevalent in ancient Iran. The production of mead, made from fermented honey, was an ancient tradition practiced by certain Iranian tribes. The honey for mead was sourced from wild bees or cultivated beehives and fermented with water, resulting in a sweet and intoxicating drink that held both cultural and ritualistic significance

Historically, ancient Persians explored fermentation techniques beyond grapes and honey. They utilized various fruits, including pomegranates, dates, and figs, to create fruit wines and alcoholic infusions. The exact methods and recipes for these early fermented drinks have been lost over the vicissitudes of time. However, the presence of archaeological remains and historical accounts confirms that the production and consumption of alcoholic beverages had a long and established history in ancient Iran, reflecting the significance of these drinks in the cultural and social fabric of the region.

Wine In Zoroastrian Tradition

Pure grape wine plays a central role in Zoroastrian religious rituals. Avesta Madho (Sanskrit Madhu) was used for various religious rituals. The Nirangistan (a Pahlavi book of rituals) refers to Mae (mild wine) and Hur (strong wine) to be used in various religious ceremonies. According to the Dinkard (a Pahlavi text), one day, Kae Vistasp asked Zarathushtra for four boons:

- To see and know more about the other (spiritual) world;

- To live forever;

- To become invincible in battle;

- To be able to see into the future.

Zarathushtra explained to Kae Vistasp that all four boons cannot be granted to any one individual. Hence, he proceeded to perform the dron ceremony consecrating wine, milk, a flower, and a pomegranate. Zarathushtra gave the consecrated wine to Kae Vistasp to drink and the latter’s soul travelled to the other world and saw his place in it. The consecrated milk was given to Peshotan who on consuming it became immortal. When Jamasp was asked to smell the flower, he became a clairvoyant and could look into the future. The Jamaspi is said to be the work of this sage. Asfandiar ate the consecrated pomegranate and he became bronze bodied (Rooyintan) and thus virtually invincible in battle.

Also, during the Sasanian era, an important and historic spiritual exercise was undertaken during the reign of Ardashir Babagan to spiritually transport the soul of a pious priest named Arda Viraf into the spiritual world. It is said, the pious Arda Viraf entered an Atash Bahram called Adar Khordad (Fire of Perfection), offered prayers, and drank a special consecrated wine. Thereafter, he went into a spiritual trance for seven days, with forty thousand priests sitting around him, offering prayers, and keeping a round-the-clock vigil.

Arda Viraf is probably the first human being to have experienced what a human soul undergoes at the time of death, traverse the different spiritual regions and return to the physical body, after a long span of seven days. It was a miracle which rekindled the faith among Zoroastrians in early Sasanian Iran.

- Celebrate Navruz 2025 With The Spirit Of Excellence And Wholesomeness - 15 March2025

- Celebrating Women And Equality - 8 March2025

- How The Greeks Viewed Ancient Persians - 1 March2025