In recent times, we have unfortunately reduced the term Gambhar to a travesty. There are Gambhars hosted by individuals who possess political aspirations and are power-hungry to use Gambhars as a platform to entice the ever-hungry community, which generally gauges the candidate’s worth on the quality of the patru!

There is also the ‘fee no Gambhar’, usually a regular dinner with a ‘cover charge’ that follows an event. This sort of Gambhar is mainly to entice people to come for the event – generally the kind where there are a few boring speakers and lots of garlands and shawls being exchanged. Sometimes, in order to manage the crowds, there is even a Gambhar meant only for men or only for women.

There is also the ‘fee no Gambhar’, usually a regular dinner with a ‘cover charge’ that follows an event. This sort of Gambhar is mainly to entice people to come for the event – generally the kind where there are a few boring speakers and lots of garlands and shawls being exchanged. Sometimes, in order to manage the crowds, there is even a Gambhar meant only for men or only for women.

From what was once a solemn, religious event, we have reduced it to nearly a comedy circus where tickets are sold in black; people scream and shout and push each other as if they have just returned from famine-stricken areas! Therefore, perhaps, it is time for us to understand the true importance and significance of this solemn event.

Gambhar means ‘the time for collecting/storing’. Broadly speaking, it is the time for collecting good deeds and Nature’s blessings. In modern times, a number of philanthropic Parsi and Irani Zoroastrians sponsor ‘Gambhar’ in the Nayat (memory) of their dear departed as an act of spiritual merit and to invoke blessings from and for the departed.

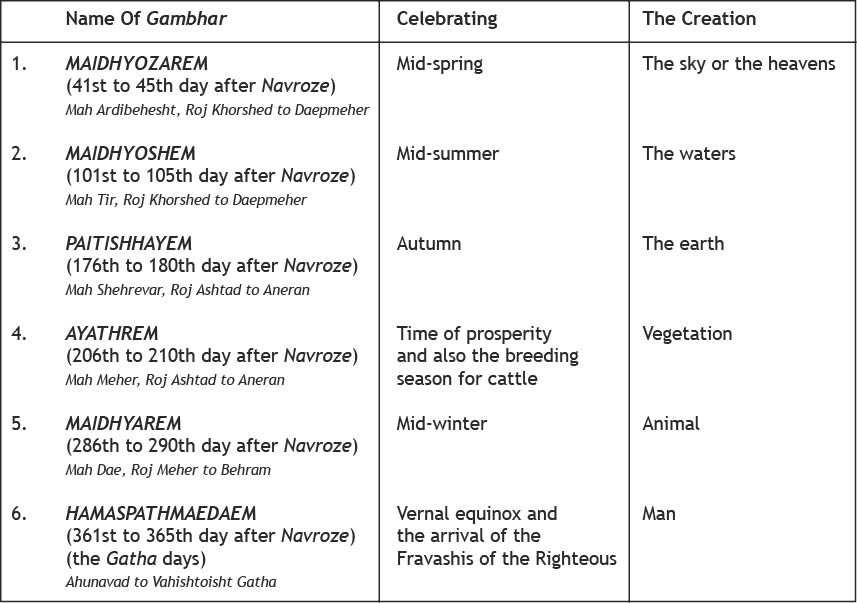

In the religious and traditional context, there are six Gambhars (in ancient times, the six great holidays of five days’ duration each in a year – the first four days of each Gambhar for preliminary preparation and the last day for the main feast). Gambhar were meant to be celebrated at a particular time during of the year to commemorate:

- The seasons and their regularity on which the prosperity of the world depends; and

- Ahura Mazda’s Good Creations in the order of their evolution.

The table given below lists the six Gambhars, the correct time during the year when these should be celebrated and the corresponding season or creation it commemorates:

According to our ‘Rivayets’, a Zoroastrian has six important duties to perform:

- Perform or participate in the six Gambhar;

- Consecrate the Rapithvin;

- Offer worship to Sarosh Yazata;

- Remember the Fravashis of the departed;

- Recite the Khurshed and Meher Niayeshes thrice a day;

- Recite the Mah Bakhtar Niyayesh at least thrice a month.

The ‘Minokherad’ (chapter IX) lists seven principal acts of righteousness, of which the first three are charity (Radih), Truth (Rastih) and celebrating Gambhar.

The ‘Shayast la Shayest’ and the ‘Sad-dar’ place the celebration of Gambhar on top of the list of religious acts of merit.

The ‘Bahman Yasht’ (‘Zand-e-Vohuman Yasna’) states: “It will be an evil day for the world when the Gambhar are not celebrated” (i.e., it will be an evil day when Zoroastrians fail to offer thanks to Ahura Mazda).

King Jamsheed of the Peshdadian dynasty is believed to have established the tradition of celebrating the Gambhar.

King Jamsheed is also believed to have initiated the tradition of wearing the Kusti, and the six tassels at the end of the Kusti provides the wearer (of the Kusti) the merit of associating himself/herself with the goodness of the six Gambhar.

There are two components of celebrating the Gambhar:

- Liturgical services (which include the Afringan, Baj, Yasna and Pavi of Gambhar) and

- Feasting (Gambhar-ni-chasni).

Traditionally, Zoroastrians contribute cash, grain, wine or manual services for the Gambhar. The poorest of poor may contribute a token piece of wood or fuel for cooking.

According to the ‘Shayast la Shayest’, on returning from a Gambhar, a Zoroastrian should recite 4 Yatha Ahu Vairyos (the priests recite 4 Yathas before the Afrin of Gambhar).

The tradition of celebrating the Gambhar at the proper time should be revived wherever a reasonable number of Zoroastrians reside. According to tradition, during the Gambhar days, Ahura Mazda showers special blessings (energies) on His creations. By performing ceremonies on that day, we invoke and tap and channelize these energies for the prosperity and happiness of the entire universe. Also, traditionally, at a Gambhar, the rich and poor sit at a common lunch or dinner table, breaking all barriers of rank and class. Doubtlessly, a community that prays and feasts together stays together. But, conversely, a community that only believes in feasting without gratitude or thanksgiving portends a bleak future!

- Celebrating Women And Equality - 8 March2025

- How The Greeks Viewed Ancient Persians - 1 March2025

- Moon And Moods - 22 February2025