Recent archaeological findings have shed new light on the history of Yazd, the UNESCO-registered oasis city in Central Iran, which houses a Zoroastrian population, proposing that its antiquity could be much further dated, than supposed earlier.

Recent archaeological findings have shed new light on the history of Yazd, the UNESCO-registered oasis city in Central Iran, which houses a Zoroastrian population, proposing that its antiquity could be much further dated, than supposed earlier.

As per a news release in Tehram Times, archaeologists believe that potteries recently excavated in Yazd, could belong to the Parthian era (247 BC – 224 CE). The potteries were found during ongoing restoration works on qanats (subterranean aqueducts). Yazd province’s Tourism Chief announced last week that if the archaeologists’ hypothesis is proven, the history of Yazd would in effect, date back to pre-Islamic times. “Our archaeologists attribute their history to the Parthian period, but this hypothesis must be proven. So, we need a license to conduct a comprehensive archaeological survey,” he said.

It is widely believed that Yazd had probably been an area of transit, rather than an area for the emergence of the prehistorical settlements, based on its arid climate and severe water scarcity. The oasis city of Yazd is wedged between the northern Dasht-e Kavir and southern Dasht-e Lut, on a flat plain ringed by mountains. Its historical structure enjoys a harmonious religious architecture that dates from different eras.

Described as the ‘Noble City of Yazd’ by Marco Polo, Yazd is widely believed to date from the 5th century CE. It stands on a mostly barren sand-ridden plain, about 4,000 feet (1,200 meters) above sea level.

Since Sassanian times, Yazd has been famous for beautiful silk textiles that were rivalled in later periods only by those of Kashan and Isfahan. The city is still a major center of silk weaving and is known for its winding lanes, forest of badgirs (windcatchers), mud-brick houses, atmospheric alleyways, and centuries of history. The city has an interesting mix of people as well, 10% of whom follow the ancient Zoroastrian religion.

Yazd is a living testimony to the intelligent use of limited available resources in the desert for survival. Water is brought to the city by the qanat system. Each district of the city is built on a qanat and has a communal center.

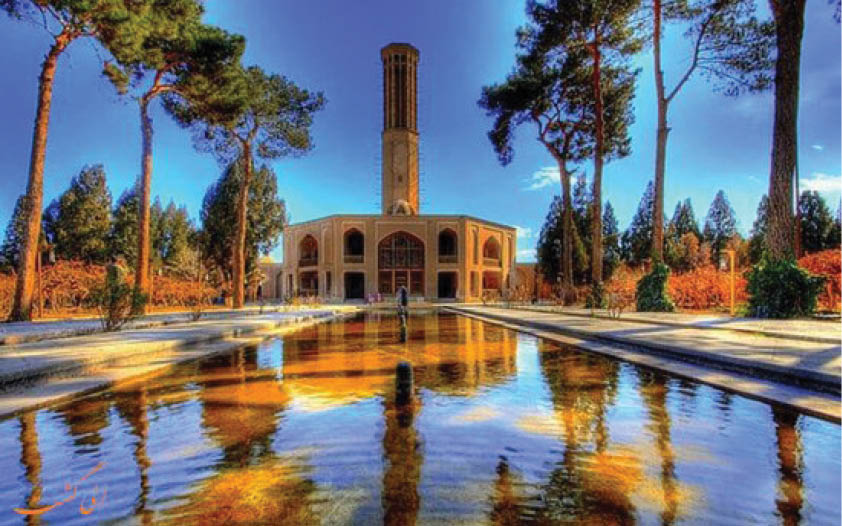

The use of earth in buildings includes walls and roofs by the construction of vaults and domes. Houses are built with courtyards below ground level, serving underground areas. Wind-catchers, courtyards, and thick earthen walls create a pleasant microclimate.

Partially covered alleyways together with streets, public squares and courtyards contribute to a pleasant urban quality. The city escaped the modernization trends that destroyed many traditional earthen cities. It survives today with its traditional districts, the qanat system, traditional houses, bazaars, hammams, water cisterns, mosques, synagogues, Zoroastrian temples, and the historic garden of Dolat-Abad.