For Zoroastrians, the desert province of ‘Yazd’ (meaning God), located between two great deserts – Dasht-e Kavir and Dasht-e Lut, holds tremendous significance. From my very first time visit in 1995 to my recent visit this year, I remain amazed at how such an unforgiving arid desert can exude so much spiritual energy.

For Zoroastrians, the desert province of ‘Yazd’ (meaning God), located between two great deserts – Dasht-e Kavir and Dasht-e Lut, holds tremendous significance. From my very first time visit in 1995 to my recent visit this year, I remain amazed at how such an unforgiving arid desert can exude so much spiritual energy.

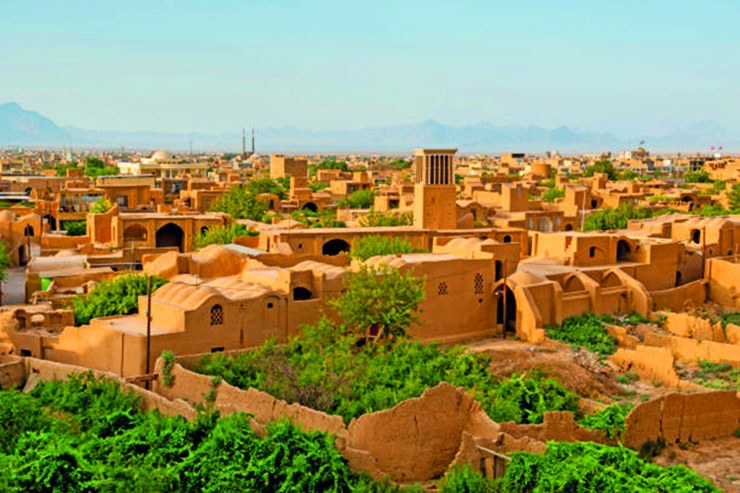

The narrow plain of Yazd, surrounded by mountains and deserts, has harsh climate, with extremely dry and hot summers and cold winters. Scanty rainfall keeps the plain partly desert – in some places glittering white with salt, in others, covered by shifting, engulfing sands. With Kerman and Fars to the south and Esfahan (or Isfahan) to the West of Yazd, the highest mountain is Shirkuh (Milky Mountain), named so due to the perpetual snow-cover, even during summer.

To beat the summer heat, Yazd residents have badgir, or wind-towers, an ancient method of air-conditioning. The construction of badgir and qanat (or the long, underground tunnels which bring cool waters of the melted snow from the mountains, and also feed underground water tables to the parched desert regions, without evaporation), is a skill known only to a few families of Yazd and is reportedly a Zoroastrian invention. In the days of persecution, Zoroastrians would travel across villages through these qanat.

Marco Polo, the first tourist to visit Yazd in 1272 AD, described it as a habitable city with “intelligent, brave and talented people.” He also wrote about its fine silk-weaving industry.

Indeed, beyond its ecological and geological wonders, this desert province has profoundly impacted Zoroastrian culture and spirituality. Mixed with the salt and sand of this desert province are stories of faith, stories of courage and stories of resilience of a people who refused to give in easily, who withstood intense torture and humiliation.

Yazd is truly symbolic of hope and faith, amid nothingness!

A Zoroastrian Bastion

A Zoroastrian Bastion

Although inhabited by Zoroastrians since the Sasanian era, after the Arab conquest of Iran, many more Zoroastrians migrated to Yazd from neighboring provinces. Due to its secluded desert setting and challenging access, Yazd was mostly spared from major conflicts and the devastation and havoc of warfare.

In her engrossing book, A Persian Stronghold of Zoroastrianism, Prof. Mary Boyce states, “… the Arab conquest of Iran in the seventh century AD was not achieved by a few great battles, but took more than a generation to accomplish: and that, although Islam was established thereby as the state religion, it needed some three hundred years, or nine generations, for it to become the dominant faith throughout the land… but late in the ninth century the tide began to ebb swiftly for the Zoroastrians… the only two places where Zoroastrians succeeded in maintaining themselves in any numbers were in and around Yazd and Kerman”.

Today, for Zoroastrians, Yazd represents a place of spiritual awakening and enlightenment. Its vastness and isolation provides a space for introspection, meditation, and a deep connection with nature and one’s ancestral roots. In most religious traditions and cultures, overcoming the challenges of the desert is symbolic of spiritual growth and transformation. Most Zoroastrian pilgrims experience a deep sense of spiritual awakening at certain mountain shrines and even the physically unfit miraculously find the strength and energy to climb steep mountain cliffs!

Zoroastrian Villages And Holy Shrines

The villages of Yazd have a mystique of their own. The beauty and charm of these villages lie in their simplicity, spontaneity, and total harmony with the natural surroundings. The architecture of the villages is standard – plain mud-houses generally well-furnished from within, with a courtyard. Some even have fish ponds and pomegranate trees. The rooms have natural cooling systems and openings in the roof for natural light to filter in. The inhabitants are warm and friendly, welcoming fellow Zoroastrians tourists or pilgrims with their legendary hospitality and grace. At these villages, glow ancient fires with mysterious origins, with dedicated care-takers of these fires. These villages also have ancient and holy Cypress trees with lots of folklore.

The mountain shrines, known as Peer (Persian for old/ancient), consist essentially of sacred rocks in high, isolated places. According to folklore, after the defeat of Yazdagird III – the last monarch of Sasanian Iran, by Arab invaders, his family fled from the palace and were separated, having to roam about in the wilderness, with the invaders in hot pursuit of Yazdagird’s wife and daughters. When everything seemed lost, the Queen and princesses prayed to Ahura Mazda for help, whereupon the mountains opened and took them in. While these stories may seem far-fetched for many, for Iran’s Zoroastrians, these are an article of faith.

Prof. Mary Boyce, in ‘A Persian Stronghold of Zoroastrianism’, writes, “These sanctuaries were very dear to the Zoroastrians, so much so that one explanation which they gave for their seemingly miraculous survival as a community was that they had been spared ‘for the sake of those in the hills’, that is, so that they might continue to worship at these remote places, and to maintain the rites which were proper to them… The five sanctuaries and one other in the plain near the city of Yazd, were in communal trust. Each village looked after the shrines in its own fields and lanes, but all joined together to care for these six. To visit any of them on any occasion was an act of much merit, but the merit was greatest when one joined in the yearly pilgrimage at the time appointed. Each pilgrimage lasted officially for five days, like each of the major festivals.”

Migratory Divide

Both, Parsi and Irani Zoroastrians are ethnically of Persian (Iranian) origin. Parsis, who came to India, about 300 years after the fall of the Sasanian Empire (around 10 AD), trace their ancestry to the province of Khorasan (ancient Parthia in North Eastern Iran). An erstwhile Zoroastrian bastion, the city of Mashad, in Khorasan, was a major oasis along the ancient Silk Road and is colloquially called the city of Ferdowsi as it houses the Mausoleum of Ferdowsi Toosi. Irani Zoroastrians (mostly settled in Yazd and Kerman) stayed on in Iran, despite severe persecution by Arabs, Turks, Mongols and other marauding invaders, over several centuries, after the Parsis had settled in India.

Unbelievable Hardships

The condition of Zoroastrians who stayed back in Iran, was miserable. In 1511, they wrote to the Parsis in Navsari, that since the reign of Kaiomars (the first legendary king of the pre-historic Peshdad Dynasty), they had not endured such sufferings, even under the execrable rule of Zohak, Afrasiab, Tur and Alexander!

One of the harshest concomitant circumstances of the conquest of Iran by the Arabs was the Jizia tax. Muslims were the only community exempted from this religious tax – all the other ‘infidel inhabitants’ of the Kingdom – Armenians, Jews and Zoroastrians – were subject to it. However, among minorities, Zoroastrians were the worst hit. Jizia was a tax ‘non-believers’ (i.e. non-Muslims) had to pay in order to practice their own religion.

Writes Prof. Edward G. Browne, in ‘A Year Amongst the Persians’ (the year being 1887-88): “Up to 1895, no Parsi was allowed to carry an umbrella. Up to 1895, there was a strong prohibition upon eye-glasses and spectacles; up to 1885 they were prevented from wearing rings; their girdles had to be made of rough canvas, but after 1885, any white material was permitted. Up to 1896, Parsis had to twist their turbans instead of folding them. Up to 1898, only brown, grey and yellow were allowed for body garments but after that, all colours were permitted, except blue, black, bright red or green. There was also a prohibition against white stockings and up to 1880, Parsis had to wear a special kind of peculiarly hideous shoe with a broad, turned-up toe. Up to 1885, they had to wear a torn cap, up to about 1880, they had to wear tight knickers, self-coloured, instead of trousers. Up to 1891, all Zoroastrians had to walk in town and even in the desert; they had to dismount if they met a Mussalman of any rank whatsoever.”

Ties Renewed

Fortunately, around the end of 15 AD, ties, so long broken between the Zoroastrians of Iran and India, were renewed. In a letter to the Parsis of India, dated September 1, 1486, Nariman Hoshang wrote from Sharifabad, declaring that all Irani Zoroastrians had been wanting for centuries, to know if any of their co-religionists still existed on the other side of the world.

Parsis settled in India were shocked to learn that while they prospered in India, their poor Irani brethren in the spiritual Motherland, suffered. A ‘Society for the Amelioration of the Conditions of the Zoroastrians in Persia’ was founded and the valiant Maneckjee Limji Hataria was dispatched as an agent of the Society. In 1854, Hataria reported the number of Zoroastrians in Yazd to be around 6,658 while 450 lived in and around Kerman. Only 50 Zoroastrians lived in Tehran and few in Shiraz. At about the same time, the Parsis in Bombay numbered 110,544. Hataria struggled against oppression of every sort and in the year 1882, he succeeded in getting the hated Jizia tax abolished.

- In Search Of The Soul - 5 April2025

- Why Pray In A Language We Do Not Understand? - 29 March2025

- Celebrate Nature’s New Year With Purity And Piety of Ava - 22 March2025