Parsi Zoroastrians have carved a niche for themselves in the country… from leading industrialists like Ratan Tata and Godrej to an army of talented Bollywood actors, prodigal Parsis are an asset to India’s culture and economy. With a population of less than 55,000 Parsi/Irani Zoroastrians in India, our lip-smacking food, peculiar surnames, stellar Bollywood movies, acting skills and the sweet mentions – from ‘dikra’ to ‘gadhera’ – are a part of India’s popular culture, but our expertise and contribution to the fashion world is lesser known… more specifically, the Art of Parsi Embroidery. Parsi Times is delighted to present the second part of the Feature Series – ‘Parsi Embroidery: A Heritage Of Humanity’ – a labour of love and much research, by Dr. Shernaz Cama, the Director of the UNESCO Parzor Project for the Preservation and Promotion of Parsi Zoroastrian Culture and Heritage, sharing the vibrant history of Parsi embroidery.

.

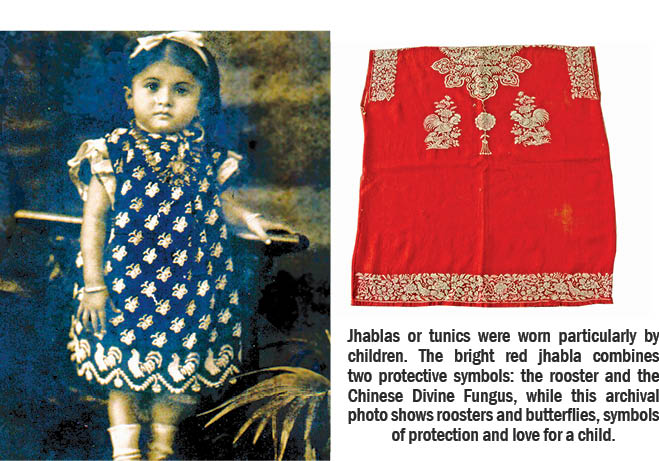

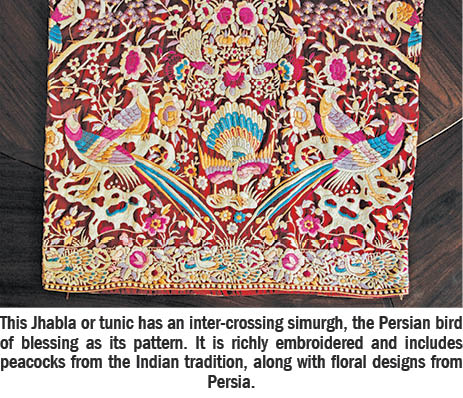

All Creation is ultimately positive and helpful. It is an optimistic creed which has helped keep a very small, scattered people active across centuries and across several diasporas. This iconography comes to life in traditional Parsi embroidery. Flowers, birds and animals are celebrated as emblems of power, protection and purity. The simurgh and rooster, sacred birds give health and protection. In its long history, Chinese symbols entered these textiles and gave to them the ‘Divine Fungus’ which like the Turkish emblem removes the ‘evil eye’.

In the Zoroastrian Text of Creation, each day is dedicated to an angel, symbolized by a flower. So, the red 100-petalled rose stands for Din – Angel of Religion; the Marigold for Atar – Angel of Fire; the white Jasmine for Vohu Manah – The Good Mind.

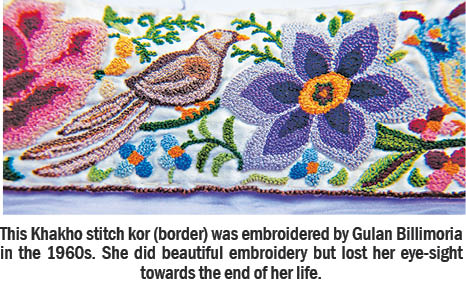

It was in the Tang and Song dynasties that this Persian love of nature, mingled with the skill of the embroidery schools of China across the Silk Route. In this early stage of intercultural amalgam, the Khakho or seed pearl stitch developed, which has minute work like the Pekin knot. This khakho or ‘forbidden’ stitch, is a lost stitch, no longer practiced. It did result in women losing their eyesight and hence its name.

The China connection with Persia was an overland trade link; this would change into a sea trade link with the later Indian Parsis. The first Parsi set sail for China in 1756. For almost 200 years, Parsi traders prospered, trading at Canton, Macao, Hong Kong and Shanghai. The Chinese had begun exporting their superb embroidery to Europe as early as the 13th century AD. Legend has it that a Parsi trader in Canton, watching craftsmen embroider a rich textile, requested them to embroider 6 yards of silk as a sari for his wife in India. These pieces often carried Taoist and Buddhist symbolism of protection such as the Divine Fungus, because embroidery in China was a sacred art.

.

* [All images are courtesy: Parzor Archives]

- દિકરી એટલે બીજી માં… - 20 April2024

- નાગપુરની બાઈ હીરાબાઈ એમ. મુલાનદરેમહેરનો ઇતિહાસ - 20 April2024

- વિશ્વ ભારતી સંસ્થાન દ્વારા રતિ વાડિયાનુંસન્માન કરવામાં આવ્યું - 20 April2024