More than two and a half millennia ago, ancient Persians were Master Maritimers. Neither the seas nor rivers stood as barriers for them, be it for trade or during war. The greater the obstacle, the more glory they saw in overcoming it. They were innovative, bold and adventurous. We narrate here how three Great Achaemenian Kings proved their genius and turned challenges into opportunities, during peace and war.

Cyrus The Great Diverts Course Of A River…

Let us start with how Cyrus the Great conquered Babylon. Ancient Babylon (modern day Iraq) was situated on the river Euphrates. The city was surrounded by massive walls considered impregnable. The river Euphrates ran through Babylon, entering and exiting through two spiked gates whose bars reached down to the riverbed. This allowed cargo ships to enter Babylon right into the city for commerce. However, when both – the outer and inner river doors were shut and all other entrances were closed, Babylon was impregnable.

How was Cyrus able to take over the city with scarcely a fight? The story goes that over a century before the birth of Cyrus, Yahweh (the God of the Jews) had promised the clairvoyant Isaiah that He would send a saviour to free the Jews who were held captive as slaves in Babylon. Yahweh had predicted concerning Babylon and the Euphrates, “I will dry up thy rivers” (Isaiah 44:27) and named ‘Cyrus’ as “my shepherd” and “anointed” (Isaiah 44:28; 45:1). Yahweh also declared: “I will open before him the two gates; and the gates shall not be shut.” (Isaiah 45:1).

When Cyrus the Great marched with his army to Babylon, he knew about this prophesy and using his intellect, he strategically diverted the course of the river Euphrates and his army marched into Babylon over the dry river-bed, while the gates were carelessly left open by the intoxicated and over confident guards, as prophesised.

Cyrus the Great freed the Jews from slavery without shedding a drop of blood and soon thereafter, gave the world the first Bill of Human Rights.

Darius The Great Digs Prototype To The Suez Canal

The Suez Canal is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. This over one 193-kilometre-long canal is a popular trade route between Europe and Asia.

The canal officially opened on 17th November, 1869, offering vessels a direct route between the North Atlantic and Northern Indian oceans, via the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea, avoiding the South Atlantic and Southern Indian oceans and reducing the journey distance from the Arabian Sea to London, by approximately 8,900 kilometres or ten days at the speed of twenty knots.

Forerunners to the modern Suez Canal included a small canal constructed under the auspices of Ramesses II. Later, another canal, probably incorporating a portion of the first, was constructed under the reign of Necho II. However, the only fully functional canal was engineered and completed under orders of Darius the Great.

The Persian King, Darius the Great (522 – 486 BCE) constructed a canal connecting the Nile to the Red Sea (an ancient precursor to the Suez Canal) that made it possible to sail from Egypt to Persia and to other places in between. The Suez inscriptions of Darius the Great are texts written in Old Persian, Elamite, Babylonian and Egyptian on five monuments erected in Wadi Tumilat, commemorating the opening of the ‘Canal of the Pharaohs’. Having conquered Egypt, Darius was also Pharaoh of Egypt.

One of the best preserved of these monuments is a stele (a stone column with inscriptions) of pink granite, which was discovered by Charles de Lesseps, Ferdinand de Lesseps’s son, in 1866, thirty kilometres from Suez near Kabret in Egypt. It was erected by Darius the Great, king of the Achaemenid Empire (or Persia). The monument, also known as the Chalouf stele (Shaluf Stele), records the construction of a forerunner of the modern Suez Canal by the Persians.

The inscription states: “I am Darius and I am a Persian. Setting out from Persia I conquered Egypt. I ordered the digging of this canal from the river that is called Nile and flows in Egypt, to the sea that begins in Persia. Therefore, when this canal was dug as I had ordered, ships went from Egypt through this canal to Persia, as I had intended.”

Many of us (including this writer) have enjoyed the Bosporus cruise while in Istanbul in Turkey. As we all know one part of Istanbul lies in Europe and the other part lies in Asia. Istanbul’s European part is separated from its Asian part by the ‘Bosporus strait’, a thirty-one-kilometre-long waterway that connects the Black Sea with the Sea of Marmara, and forms a natural boundary between the two continents.

Today, two suspension bridges across the Bosporus – the Bosporus Bridge and the Fatih Sultan Mehmet Bridge, also called Bosporus Bridge II connect the two sides or the two continents of Asia and Europe. However, over 2,500 years ago, when Darius the Great tried to cross over from Asia to Europe with thousands of soldiers, the Bosporus (almost a mile wide) presented a logistical problem.

The Greek writer Herodotus says in his ‘Histories’ that, on the orders King Darius the Great of the Achaemenid Empire, Mandrocles of Samos engineered a pontoon bridge (a floating bridge) across the Bosporus, linking Asia to Europe and this bridge enabled Darius to pursue the fleeing Scythians as well as position his army in the Balkans to overwhelm Macedon.

Xerxes the Great… A Bridge Of Boats…

Ancient civilisations must have looked longingly at unreachable shores on the other side of rivers and wished for bridges to carry them there. However, wishes alone could not build those bridges, but wars could. In fact, most early floating bridges were built for the purposes of war. The Persians, Chinese, Romans, Greeks and Mongols – all used versions of pontoon bridges to move soldiers and equipment, usually across rivers too deep to ford.

The most primitive floating bridges were wooden boats placed in rows with planks laid across them to support foot traffic, horses, and wheeled carts. At each shore these bridges were secured, often with ropes, to keep them from drifting with the current or wind.

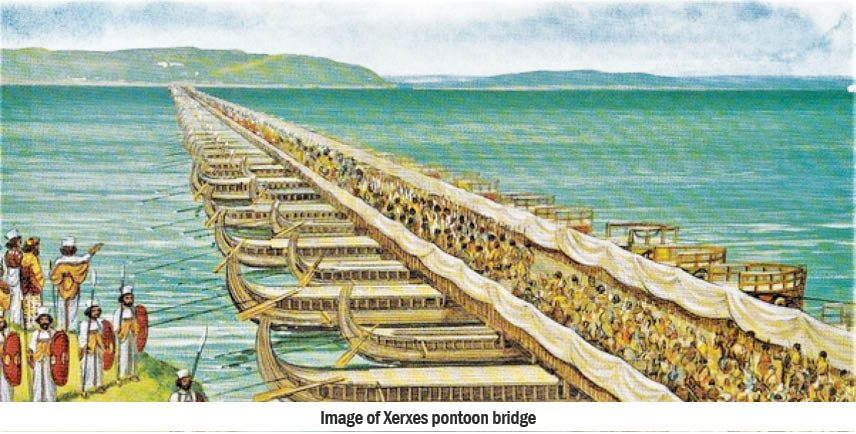

Xerxes the Great ordered a pontoon bridge to be constructed in 480 BC during the second Persian invasion of Greece to traverse the Hellespont (present-day Dardanelles) from Asia into Thrace, then also controlled by Persia (in the European part of modern Turkey). The Hellespont was a more than one-kilometre-wide strait.

The first floating bridge, built on the command of Xerxes the Great, was destroyed due to a very violent storm. However, Xerxes refused to give up and a second bridge was built, and nearly 400 ships were used to keep its surface afloat. However, according to Herodotus, the bridge was made of 676 ships stationed in two parallel rows with their keels in the direction of the current.

The boats were all tied together with heavy flaxen and papyrus ropes and weighted with heavy anchors to hold them in place. There was an opening left so that small vessels navigating the strait could still pass the bridge. Logs were used for the bridge’s surface, and these were topped with soil. There were barriers on each side so that horses and soldiers would not fall off. This bridge survived the marching of several thousand soldiers and horses across the strait and the army of Xerxes succeeded in capturing Athens.

Ancient Persians, like Cyrus, Darius and Xerxes never blamed circumstances. In fact, they did not seem to believe in circumstances. They looked for circumstances that they wanted and if they could not find them, they made them! Men such as these are called Great and remembered even after two and a half millennia, because they were innovative, bold and considered no challenge as impossible!

- The Poison of Pessimism - 27 April2024

- Celebrating The Interplay Of Life And Fire! - 20 April2024

- Customs To Observe At Atash Behram Or Agyari - 13 April2024